The Uninterrupted Work Cycle

by Regan Becker

“Each time a polarization of attention took place, the child began to be completely transformed, to become calmer, more intelligent, and more expansive.” — Dr. Maria Montessori

One of the characteristics of a Montessori classroom is an uninterrupted work cycle. Dr. Montessori discovered that children as young as three years old are able to choose productive and challenging work. Montessori studied children’s attention spans and concentration for self-chosen work and crafted an open period of time for them to explore concrete materials on the shelves, rest, have lessons with a guide, observe others working, and experience restlessness. Children develop focus when they are not interrupted.

Trinomial Cube

An uninterrupted work cycle:

promotes independence and confidence,

offers children the emotional safety to choose activities and materials that attract them or help them feel secure,

lets children discover through active observation and patience (rather than feeling obligated to passively receive information from a single source),

gives children practice setting up an activity and cleaning it up (which encourages an organized mind),

shows children that everyone learns differently and with different materials at the same time,

allows children to satisfy through slowness and repetition what they need from a material or experience without concern for arbitrary schedules,

demonstrates the benefits of a self-paced learning process, and

provides children practice with prolonged focused attention.

Knobless Cylinders

Children lack power in the world and are dependent upon adults for many aspects of their lives. The Montessori work cycle honors children’s time, space, and motivation as they are individuals worthy of respectful consideration. Children who arrive on time to start their morning work cycle and who have appointments after the school day are more likely to choose challenging work that requires increased concentration, as compared to children arriving late or leaving during the day.

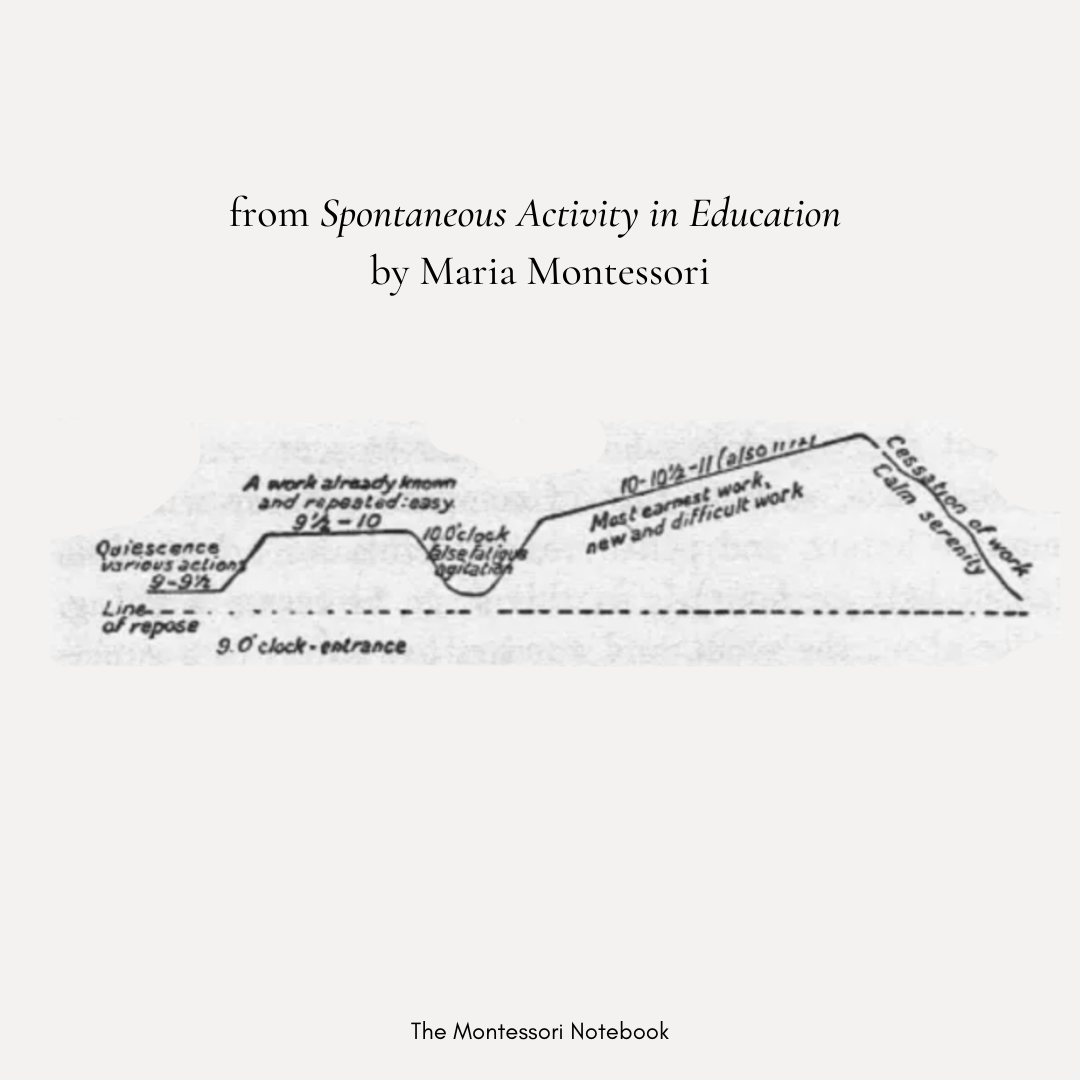

Dr. Montessori’s notes, image from themontessorinotebook.com by Simone Davies

A usual Montessori work cycle varies from 90 minutes to three hours in duration. This period of engagement is called a “work cycle” because Montessori observed that it contains stages which continue in the same way most every time:

Children visit the shelves looking for a familiar Montessori material to use independently, or a new material – for which they may request a lesson from a guide or an older student.

Adults observe and assess children’s behavior, learning interests, concentration, and underlying social and emotional needs. They redirect, guide, and invite children to individual lessons as needed.

In the Montessori classroom, children exercise freedom of movement as part of their learning journey. They may stand up and stretch or observe another student’s lesson. Children may have snack, use the bathroom, or get a drink of water whenever their bodies need these breaks. Angeline Stoll Lillard, author of Montessori: The Science Behind the Genius, wrote, “If we choose when to take breaks, then breaks work for us, but if the timing is externally imposed, breaks can be disruptive to concentration.”

Montessori coined the term “false fatigue” for a moment about an hour into the work cycle when a child rests or takes a break as a natural reaction to a lengthy period of engagement with materials and/ or lessons. Dr. Montessori wrote, “The mind takes some time to develop interest, to be set in motion, to get warmed up into a subject, to attain a state of profitable work. If at this time there is interruption, not only is a period of profitable work lost, but the interruption produces an unpleasant sensation which is identical to fatigue.” The agitation of energy at this time is a natural part of an optimal learning experience — what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called “flow” — before the final phase of focus.

The last hour of work cycle is usually when children are most likely to choose challenging work and to concentrate deeply – what Montessori called the child’s Great Work or Cosmic Task. When given ample time and space for learning, children often select work which engages and engrosses them, and they are understandably upset when a disruption takes place. Dr. Montessori wrote, “A sudden interruption is more fatiguing than persistence.” Once the child’s concentration is broken, it is very difficult to try to re-engage them with the environment.

A child waits and watches the Spindle Boxes lesson.

Children deserve the opportunity to learn at their own pace, concentrate in peace, and develop independence – all while free from unnecessary adult interruptions. Montessori guides follow the child’s schedule before their own. Adults prepare themselves to be observant, perceptive, and restrained – so that their enthusiasm and interest in the children’s work does not distract the children from their internal motivation.

Formation of Numbers

We should never disturb children who are clearly learning – even if our intentions may be to ask questions, or make unnecessary comments of approval or appraisal. We adults model to all of the children in a Montessori classroom that each child’s work is sacred. Children receive Grace and Courtesy lessons on how to Watch Someone Work (without talking or touching) and how to walk around a rug, so the physical objects are left intact.

Dr. Montessori said, "When the children had completed an absorbing bit of work, they appeared rested and deeply pleased.”